Although I now live in North London, I spent the first eighteen years of my life growing up in Northamptonshire, in the East Midlands. Northamptonshire is a strange county – it doesn’t have a city or any especially famous landmarks, and people don’t know where it is, so I’m used to the odd perplexed shrug when asked where I’m originally from.

I expect that much the same could be said for anywhere once you’ve had the chance to get to know a place, but it’s my strong belief that Northamptonshire has much more to recommend it than people give it credit for. It doesn’t really do scenery, being virtually flat and landlocked, but it does have numerous beautiful villages, and places where eccentricity seems to have been allowed to thrive unchecked.

One such place is Finedon, where my father grew up. Most Sunday afternoons during my early childhood in the 1980s, my family would make the short drive over to Finedon to visit my grandfather, my dad’s stepmother, and their daughter. In my mind these visits are always associated with the smell of coffee and the Sunday meat roasting in the oven. Or in winter, driving back in the dusk before the evening rituals began to take us into a new week of work and school.

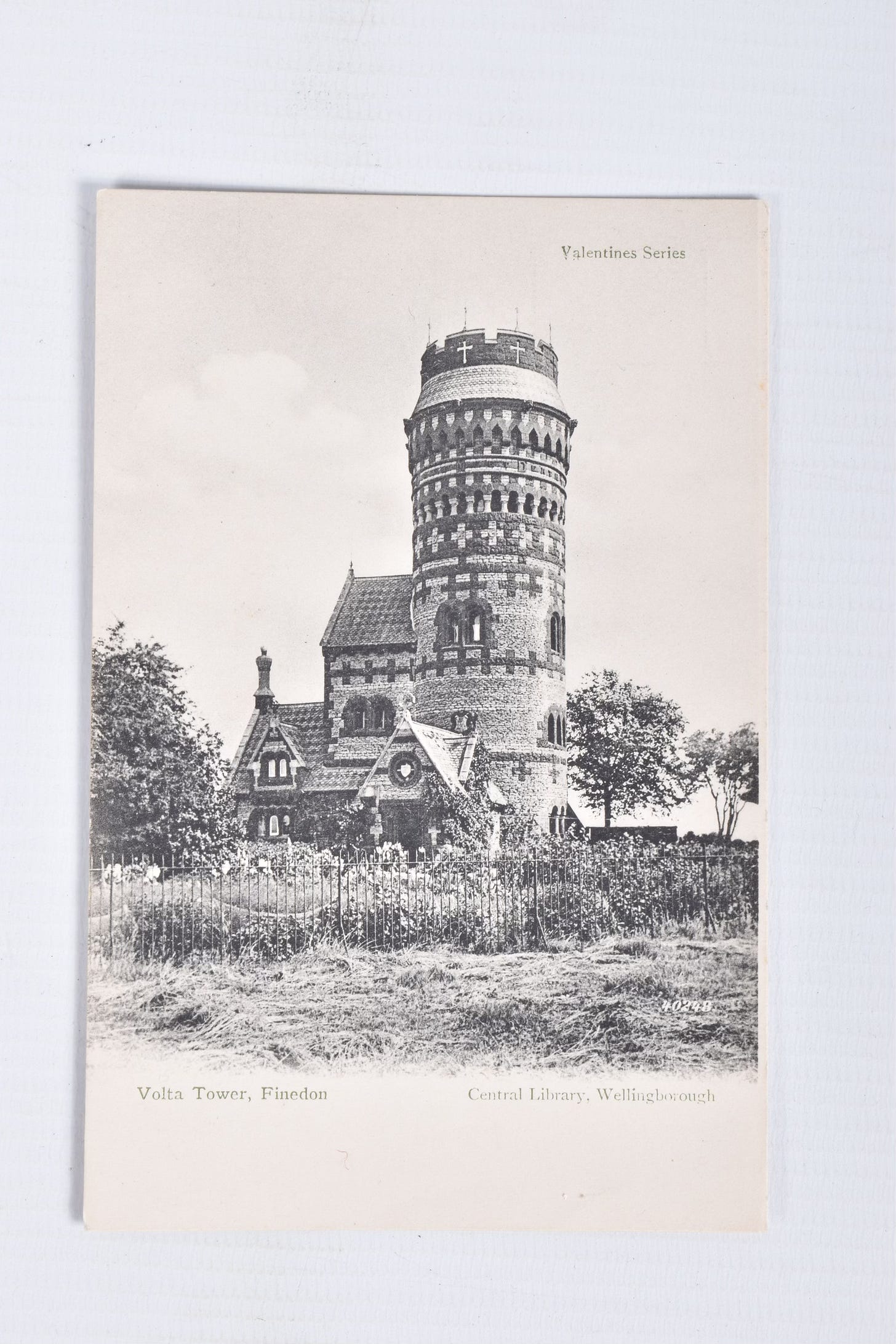

This drive was only five miles or so, but of course as a child, it seemed longer. There was little to loom on the horizon until something let you know you were nearby – the silhouette of the grand and imposing water tower.

Built in 1904 by the Northampton architects Mosley & Scrivener, the tower had been converted into a residence by the time I became familiar with it. I was mildly obsessed with this, thinking it must be such a cool place to have as a home, and certainly much more exciting than our late 1970s semi. Occasionally a light would be on in one of the lower windows, offering a tantalising glimpse into what it might be like to live inside! Pretty impractical I imagine, but that didn’t stop me daydreaming. As well as serving as a beacon that we were approaching my grandad’s house, this tower could be a way finder when travelling lesser-known roads slightly further afield – ah, there’s the tower, so we must be near Finedon, and therefore not too far from home.

But there were other towers in Finedon, some of which I only came across on longer excursions to my relatives’ house. Like many such small towns, Finedon began as an ancient manor, presided over firstly by the Mulso family, before passing to the Dolben family during the eighteenth century.

A few Dolben baronetcies came and went until eventually, the end of the male family line was reached on the death of the 4th Baronet, Sir John English Dolben, in 1837. Sir John had kicked off what seemed to become a trend of eccentric memorials and innovations, with a diminutive yet curious mini obelisk. The obelisk is situated at a crossroads and might once have displayed the distances to various other towns and cities, but is now much corroded. Its other purpose was to mark ‘the blessings of the year’ in 1789, such blessings likely including the return to sanity of King George III, for which thanksgiving celebrations were held on 23 April, including at Finedon, where they were marked with fireworks and cannon fire.

Following the death of Sir John, his surviving daughter and heiress Frances married William Harcourt Isham Mackworth, who then took the additional surname Dolben, becoming William Harcourt Isham Mackworth Dolben and beginning a succession of long and confusing family names.

William and Frances resided together at the family seat of Finedon Hall, and had four children born between 1836 and 1848. But tragedy struck in 1863 when their eldest son William Digby Mackworth Dolben, serving in the navy, was drowned off the west coast of Africa aged just 24, his body lost at sea. Distraught, his father (who also fancied himself as something of an amateur architect), set about commemorating him with a building he named the Volta Tower. Finished in 1865, this impressive Gothicised folly loomed large over the Finedon Hall estate, but crucially, was rumoured to have been constructed without the use of any mortar.

By the 1950s, the tower was being lived in by a couple, Mr and Mrs Northen. In November 1951 however it suddenly and dramatically collapsed into a pile of rubble, sending plumes of dust up into the air, and killing Mrs Northen who was inside the building at the time. My father was born a month earlier in September 1951 – so he’ll have no memory of the tower, but perhaps he felt the vibrations from its demise rattle his crib.

William Mackworth Dolben senior made several architectural changes to the Finedon Hall estate, including the building of an icehouse in around the 1850s. Located some distance from the main Hall, this tower sat in an area that would later be redeveloped into a housing estate, as the town of Finedon expanded. Thankfully, rather than being demolished or left unloved, the icehouse tower was incorporated into one of the estate new builds.

Although the Historic England listing entry for the tower rightly states that ‘the house attached to the left is not of special architectural interest’, I rather like the juxtaposition.

The final tower commissioned by Mackworth Dolben in the mid 1850s is part of the Hall range and was probably designed by local architect E. F. Law, who had also made several alterations to the main building. Tantalisingly, it is known as the ‘Museum Tower’, but I can find no record of what it once contained. Knowing what I do of private museums in country houses, it could have been any number of things such as family mementos, objets d’art, or even a cabinet of curiosities. It’s possible the sale catalogue for the 1912 auction of the Mackworth Dolben collection might shed some light, but I cannot find a copy online.

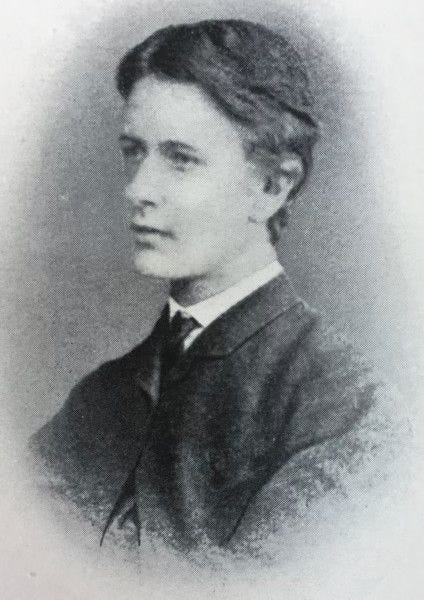

If the building of the ill-fated Volta Tower was testament to the Mackworth Dolbens’ grief for their eldest son William, we can scarcely imagine how they must have felt about what would later play out. Neither of their other two sons would survive beyond their twenties. Herbert, who like his older brother William was in the navy, died in Bournemouth in 1870 aged 29. Their youngest, Digby, drowned in the River Welland in 1867 aged 19, while swimming with the son of a tutor who was preparing him for university at Oxford.

Digby (pictured below) was an intriguing figure, and who is to say what he might have become if he had not perished so young. He was handsome, prone to dreaminess and shocked his peers by writing love poetry to an older boy at Eton. Later, he was introduced to the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, who became instantly besotted with him.

Digby was attracted to the high church, and did not enter into this enthusiasm lightly.

He became a novice in the English Order of St. Benedict, signed his letters Dominic, and was furnished with a monk's habit which he wore in public, delighting in the provocation, wearing it on one occasion through the streets of Birmingham, walking barefoot, surrounded by a mob.

(For further reading on Digby, see the longer piece from which the above is taken, The Strangely Troubled Life of Digby Mackworth Dolben.)

With all the male heirs having died young and childless, the estate passed to the Mackworth Dolbens’ only surviving child, their daughter Ellen Frances (1836 – 1912). She never married and died at Finedon Hall as the lady of the manor of Finedon, with her public philanthropy recognised in her obituary in the 1912 Birmingham Post:

Miss Dolben gave liberally to church work. She purchased the living of Finedon, and placed the presentation to it in the hands of the Bishop of Peterborough. She also gave a site for the erection of Church schools, and provided the parish with a public hall.

Following her death in 1812, Ellen left her estate of £58,907 (around £5.6m today) to be dealt with by her estate agent and solicitors.

Finedon Hall passed through several other owners, including a spell as a military education centre, but the building was falling into disrepair. It was eventually sold to developers in the early 1970s, but no works took place and by the 1980s, it was virtually derelict, the stone motto set out on its front, Gwell Angau na Chywilydd (Death rather than Dishonour), gradually crumbling away. During the 1990s, development work finally began to turn the hall and its outbuildings into apartments.

I was a teenager by this time, and I was surprised to find out that my parents were taking us on a viewing of the newly developed apartments – I think it must have been an estate agents open day. We were shown one flat in particular which incorporated a decadent, panelled room which must once have been a grand entertaining space, now proposed as the living room for prospective buyers. I was delighted, already wondering when we could move in, but actually, I think my dad just wanted to have a look around having grown up nearby. It wouldn’t have been practical for us to live in Finedon at that point, or in a flat, really. And so my own chance to follow in the footsteps of the Mackworth Dolbens never came.