A Lancastrian Grave

Towards the end of the last century, I was a student living in Lancaster, in the north of England. I had arrived there just before university courses stopped being free, and I like to think I would have done a bit more work if that wasn’t the case, perhaps treated the whole thing with a bit more gravitas. But as it turned out, like many students at the time, I approached it as a natural thing that would happen after school, a place to start figuring out who I was, my place in the world. A chance to live on my own. My degree in English Literature and Creative Writing became something of an afterthought.

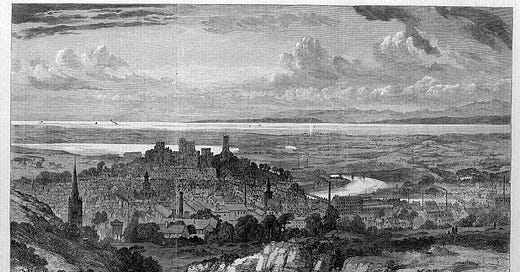

As the 1969 North Lancashire volume of Pevsner’s Buildings of England attests, Lancaster is really a Georgian industrial town, but on a medieval footprint, which the much-maligned one-way system is now forced to snake around.

One may be fascinated by many a North Lancashire town, but it is not aesthetic qualities one would remember. Lancaster remains in one’s memory for many visual beauties, the view from the N to the river and the castle and the church on their rock, the view from the castle and the church towards the bay and the fells, and the streets still in a number of cases purely Georgian. Lancaster is a Georgian town, despite its great medieval past.

A quick jaunt around Google Maps suggests Lancaster is aesthetically still very similar to the place I left nearly 25 years ago, though the university campus (which is two miles away and continues to grow) might now be larger than the size of the city centre itself. It is also a place which boasts, or did, many excellent pubs. I suppose with this much distance it’s natural that there have been a few casualties, despite Lancaster’s constant transient student population. My old haunts The Navigation (demolished), The Friary and Firkin (derelict) and The Yorkshire House (closed) are all gone. But I’m relieved to see some other old favourites such as The Merchants (where we used to do the quiz, at which there was a possibly apocryphal story about someone winning a telly) and old man jazz pub Ye Olde John O’Gaunt are still going strong.

After you wind up the hill towards Lancaster Priory Church and the castle, there is a sloping section of land which has been crafted into a sort of mini amphitheatre with tiered seating. At some point, someone decided to tidy up the presumably long-neglected tombstones of Lancaster Priory and repurpose them into the rows of seating for this area. The place was usually quiet, and I used to enjoy sitting alone up there and reading my books that weren’t on the syllabus sometimes. It felt still and had something of the view of the bay and the fells described in Pevsner, a sort of promontory on which I collected my thoughts about my young life, and maybe romanticised my future.

Sitting up there one day, my eyes chanced upon the inscription on one of these old gravestones, that I hadn’t noticed before. It said:

IN MEMORY OF

ABRAM JENNINGS who died

February the 27th 1845

Aged 27 Years

ALSO

ESTHER JENNINGS his Wife

who died December 15th 1848

Aged 28 Years

ALSO

ANN ALICE who died in her infancy

Farewell false world I’ve had enough of thee

And now am careless what thou saith of me

Thy smiles I court not nor thy frowns I fear

My cares are past, my head lies quiet here

The whole inscription looks to have been completed at the same time, and is at the bottom of the stone, so this was likely put up following the deaths of Esther and Ann Alice. Of course, young deaths in the nineteenth century were something of an occupational hazard. But even given this detail, the inscription seemed striking, like two fingers to the world. And for whatever reason, perhaps due to my own morbid tendencies, I have never forgotten it. I always wondered what the story of Abram and Esther was, and how it might have contributed to this rather bleak epitaph. And so, all these years later, I decided to try and find out.

Abram Jennings was born in Hornby, Lancashire in 1817, the eldest of seven siblings. By 1841, he was living with his widowed mother and his siblings in Bridge Street, Lancaster, and was working as a painter. Esther Parkinson was the youngest of six and was born in nearby Cockerham. By 1841 she also lived in Lancaster, on Germany Street (this street was later renamed after WWI) with her widowed mother and two unrelated fifteen-year-old girls, presumably lodgers.

The couple were married on New Year’s Day 1844, at St Mary’s Priory Church, Lancaster, the same church outside which they would eventually be buried. They then moved in together to Esther’s house on Germany Street. Tragically, just over a year later, Abram died from phthisis (likely tuberculosis). The couple had not had any children. It is unknown what happened to Esther in the intervening years, other than that she seemingly continued to live in the house at Germany Street, and did not remarry. However, in 1848, she became pregnant by an unknown man.

Ann Alice Jennings, as she would later be baptised, was born on the 8th December that year. In the days after the birth, Esther suffered complications, severe exhaustion and an ongoing stomach complaint. Just a week after the birth of her daughter, she succumbed to her illness. Her sister Ann, who worked at Lancaster Lunatic Asylum and therefore may have had some degree of nursing training, reported the death from the house at Germany Street, and was perhaps there to care for mother and child.

Ann Alice was baptised on the 19th December, the same day her mother was buried. She clung to life for just over another month, but died of malnourishment and fluid on the brain on the 21st January 1849 (it’s possible she was premature, though we can’t know for certain). Another of Esther’s sisters, Ellen, was the informant for the death, and was probably caring for the baby.

Tempting as it might be to infer all sorts of possibilities as to what tragedies in Abram and Esther’s young lives prompted the unusual inscription on their gravestone, and the circumstances surrounding Esther’s pregnancy, these are the only facts available. Perhaps we are wrong to think that this generation was, to a degree, inured to or stoic about death. Perhaps Esther never getting to build a life with her husband, and then for her infant child to follow her so quickly to the grave, in the dark months of December and January, was felt to be a loss of potential so tragic that the only assumption was that fate must have had it in for all three.

And what about the inscription itself? Where did it come from? Whilst not paupers, this was a firmly working-class extended family on both sides. They were labourers, household servants, coal heavers, shoemakers, or they worked in Lancaster’s cotton mills. There is no obvious aspiring poet or scholar lurking within the family ranks that I can find who might have suggested such a rhyme.

But perhaps the rhyme is not as rare or strange as the modern reader might think. Knowing what can happen to gravestones once they become neglected (and the one at Lancaster may well not have survived at all had it not been repurposed), and with record keeping being patchy, no survey can ever be truly comprehensive. However, I’ve discovered around ninety examples of variations on the inscription, the earliest in Cottesmore, Rutland, from 1708, and the most recent from Bradwell, Derbyshire, two hundred years later in 1908. There are examples in America, Canada and Australia, too.

The meaning becomes a little clearer when you discover that there have been other sections to the rhyme. There are a few variants, and some, like the Lancaster grave, only use the first section or a shorter combination of the other sections. The longest version incorporating them all is as follows:

Farewell vain world! I've seen enough of thee

And now am careless what thou say'st of me

Thy smiles I court not, nor thy frowns I fear

My cares are past, my head lies quiet here

What faults you saw in me take care to shun

And look at home - enough there's to be done

Where'er I lived or dy'd, it matters not

To whom related, or by whom begot

I was, now am not, ask no more of me

'Tis all I am, and all that you shall be

This version is published in A Collection of Epitaphs and Monumental Inscriptions, Historical, Biographical, Literary, and Miscellaneous, to Which Is Prefixed, an Essay on Epitaphs by Dr. Johnson (yes, that Dr Johnson), published in 1806. The date and location of the grave are not revealed, but the lines were – supposedly - ‘composed by a gentleman, for himself’. This isn’t the only time that versions of the epitaph are described as the deceased’s own composition, so we should perhaps take this with a pinch of salt.

A couple of other versions have done their own thing with the end of the verse (I particularly like ‘Farewell vain world / I've seen Enough of thee / & Careless I am What you / Can say or do to me / I fear no threats from / An Infernall Crew / My Day is past & I bid / The World Adieu’ from Cromer, Norfolk, 1755) but generally, the meaning appears to be one of heading somewhere where worldly transgressions can be forgotten, that on earth nobody is ever completely free of these, that we are all the same in death, and that death is the destination towards which we are all eventually heading. The classic ‘memento mori’.

At some point, the verse acquired an association with a couple of ne’er-do-wells. It was supposedly found by the body of the murderer Mungo Campbell after he hanged himself in Newgate Prison in 1770. Four years later, in 1774, John Upson, of Woodbridge, Suffolk, hanged himself in his prison cell with his garter, with the verse recorded as being written in a prayer book lying near him.

Despite these more macabre associations, there’s nothing to infer from the ages of the deceased on whose graves the inscription is used. It isn’t the preserve of younger occupants with an untimely end, such as Abram and Esther. William Sayer, for instance, made it to the age of 100, which was no mean feat in 1822. His grave is in Wingham, Kent. The county of Kent has the most examples of the inscription and its variants that I can find, either because there genuinely were more of them there (the idea having spread by proximity or word of mouth) or because the historians of Kent have just been better at documenting them.

But even proximity couldn’t guarantee a faithful rendering. There are two versions of the inscription in the churchyard at Greasley, Nottinghamshire, one from 1756, for William Harvey, and another for Phillis Robinson over a hundred years later, in 1866. The latter is mentioned in an edition of Notes and Queries (which in the nineteenth century functioned something like an analogue version of Reddit), and which occasionally collected unusual epitaphs. Phillis’s version of the inscription has become: ‘Farewell vain world I've had enough of the / I doent value what thou can see of me / Thy frowns I quote not, thy smiles I fear not / Look at home and theirs enough to be done’. As a correspondent to Notes and Queries points out, ‘its fearful and wonderful rendering possibly is due to the circumstance that it was chiselled from memory by an extremely illiterate man’.

As well as the Samuel Johnson volume mentioned above, the inscription does get included in several other volumes as being curious or unusual, even while it was still being used. Perhaps it was misunderstood or even interpreted in different ways at the time. It’s plausible that one of these publications is how the grieving Jennings and Parkinson families in Lancaster came across it, although it seems unlikely. There is a mention in a contemporary Notes and Queries of there being an example of the inscription in nearby Preston, but I can find no present-day record of it.

There is one unique thing about the verse on Abram and Esther’s stone in comparison with the others I have found, though. It is the only example where the world is described as ‘false’ (rather than ‘vain’). Whether this is a misremembering or a deliberate alteration, it is impossible to know, but I feel it lends a slightly more mournful tone, that how fate treated them perhaps meant the world became somewhere they were not entirely hesitant to leave.

Writing this down at this time of year, when it is said that the veil between worlds is at its thinnest, I find it both sad and comforting to remember Abram, Esther and Ann Alice, even though I know so little about them, and can only imagine their lives in the familiar Georgian streets where I also spent some of my young life, albeit in entirely different circumstances. Their unusual epitaph is the only reason I have had cause to do so, and I wonder whether this ever occurred to or motivated those who chose it. It ensured that I connected with them, that I remembered them. I hope that their heads lie quiet, wherever they are.